This work is old and due to current strict regulations, it may not be possible to republish the visuals and stories as they are.

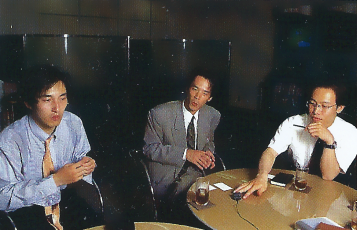

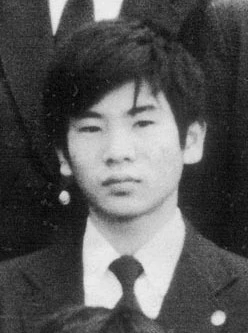

Takashi Miyamoto

Moonlight Syndrome is the fourth and final game that Suda51 directed during his stay at Human Entertainment. While it is the foundational piece of his Kill the Past mythology, it’s impossible to discuss it without first addressing his previous outings for the company.

NOTE: The Syndrome games were never officially translated. Subtitled playthroughs are available in Bonus Footage.

His debut in the videogame industry was Super Fire Pro Wrestling III, released for the Super Famicom in 1993, surprisingly under the role of director. Suda’s only experience in the industry, up to that point, was working as a graphic designer in Sega AM-2; he was, however, a devout hobbyist. Being a child of divorce, lacking a higher education and having married young, not to mention having to support himself and his wife in Tokyo since leaving his hometown of Nagano, he’d take on any job that was available to him without even attempting to build a career in an industry he was passionate about.

He was working as a funeral director when his wife finally convinced him to send applications to Human Entertainment and Atlus, the two companies who would accept applicants without any prior experience. Luck would have it that, despite failing his initial interview at Human, they were in desperate need of an expert in Professional Wrestling due to the sudden resignation of Fire Pro III’s planner, which is how he ended up being called back and entrusted the role of director.

Halfway through development, his supervisors decided that he accumulated enough experience to independently complete development; however, as a director, Suda still felt like he should be building the game to be as similar as possible to its predecessors. It wasn’t until the following year, with the departing producer Shuji Yoshida and Suda’s own mentor Masato Masuda both encouraging him to build the next game as he saw fit, that his identity as a creator began to coalesce with the release of Super Fire Pro Wrestling Special.

Suda’s most known contribution to the franchise is Special’s controversial story mode; however, it is worth noting that he also spearheaded some major gameplay changes that are still used in the series to this day: Fire Pro’s gameplay revolves around grappling, specifically timing button presses to the animation that plays out when two wrestlers clash, as internal calculations decide whether a weak, medium or strong grapple will succeed or fail in order to simulate the flow of a booked wrestling match.

However, the animations, up to that point, were severely limited, making it extremely difficult to time your grapples, with III being an egregious example, to the point of needing a simplified re-release the following year under the title “Easy Type”. Moreover, Suda felt the level of abstraction was too high for players to properly immerse themselves in the game. As such, under his direction, the animations were completely overhauled, making the game more intuitive and realistic. He also touched up the game balance, surprisingly making it more skewed, in order to properly replicate fights between wrestlers of different weight classes and ability.

Another big change was the inclusion of a single-player, story-driven campaign, “Champion Road“, which Suda himself wrote. This was done in an attempt to bring a wider audience to the Fire Pro series, which had been seen as a multi-player experience up to that point.

What’s surprising, however, is that the campaign turned out to be a dour, scathing critique of the then current world of Pro Wrestling, with its depressed, unstable main character, Morio Sumisu (a play on “Morrissey” and “Smith”) making his way through the divided and corrupt world of Japanese and international promotions of the 80s and 90s. Following Masuda’s tradition, Special also utilizes fake names for each wrestler and promotion, but most of the events that inspired its scenario were very real.

Moreover, the game ended on a very sudden and shocking note; as Suda explained in this Automaton interview, said conclusion was originally implemented as a “bad ending” which would trigger if the player lost the final match. However, he felt that letting a binary game system decide matters of life and death would be nonsensical, so the “good ending” was removed.

While his bosses did not complain about the scenario, possibly because they didn’t play the game at all, after it was unleashed on the public in December of 1994 Human Entertainment was flooded with postcards asking for Suda’s head or at least a full refund, with less than 10% of positive feedback.

This was, perhaps, an omen of things to come.

His very next project would be Twilight Syndrome, an adventure game centered around a trio of high school girls: Yukari Hasegawa, Mika Kishii and Chisato Itsushima, investigating paranormal apparitions in their home town of Hina-shiro. The basis for the project was to adapt the 3D sound technology that Human had previously employed in Arcade cabinets to home consoles, the idea of using a haunted horror setting being chosen specifically to accommodate it.

More specifically, Twilight Syndrome was going to evoke the feeling of sharing ghost stories in school, with some of its chapters being based on actual rumors (most notably Hanako-san). Suda mentioned Gakkou de atta Kowai Hanashi as a direct inspiration, but sharing occult rumors was actually a very popular summertime activity in 90s Japanese youth and went on to inspire a variety of other media.

Suda was not initially assigned to the project, but his predecessor, Keita Kimura (developer of Septentrion), had a mental breakdown during development and Suda, while harboring some reservations due to his own fear of ghosts, pitied him and the rest of the development team and ultimately decided to step in as director to prevent the game from being cancelled (in his words “I felt I had no choice but to wipe his ass”).

According to him, development had reached a breaking point by the time he was brought in; The game was planned to have ten scenarios, but only seven had been conceptualized and only three had been completed, with only three months left of development time. However, the game’s assets had already been constructed, so unlike his experience with the Fire Pro games (for which he had to be involved on every stage of development, from planning to data insertion) his role as “director” was better defined and it mostly involved managing the assets that were already in place and expanding on what was already done.

It should be noted that Twilight Syndrome had a certain publicity push, with a radio program, a tie-in manga and a Drama CD having already been produced to promote the game; for this reason, missing the release date was not an option. That’s why the game ended up being split in two halves:

Tansaku-hen (Search chapter), which came out in March of 1996, was made up of the three scenarios that were completed under Kimura’s direction (“The Original Rumor”, which served as the game’s prologue, “Ghost Photo Mass Production Park” and “M.F. of the Music Room”, the first and second chapters respectively) and two of those that were conceptualized, but not completed, “Last Train” and “Seven Mysteries of Hina-shiro High School”.

The game ends on a fully original teaser, “One More Rumor”, which leads directly into the first chapter of Twilight Syndrome’s second half, Kyuumei-hen (Investigation chapter), which released in July of the same year.

At this point, four of the seven conceptualized chapters had been used, meaning that more than half of Kyuumei-hen had to be written from scratch. Suda did not serve as scenario writer for Twilight Syndrome; Hiroshi Kasai was its main writer, and was accosted by Mika Mishima, who’d mostly touch up the girls’ dialogue to make it more realistic, but also served as the sole writer for “Telephone Call”.

Kasai has elaborated in an X memorandum (Archive) on which chapters were created under Suda’s direction: “Hinashiro’s Grove”, the game’s fifth chapter and Kyuumei-hen’s opening, picking up directly from the “One More Rumor”, was fully original, and also happens to be the most important one when going into Moonlight Syndrome. “Telephone Call” and “Occult Mystery Tour”, the seventh and ninth chapter respectively, were also conceptualized under Suda, and were simpler scenarios based around efficiently using the assets already in place (such as Yukari’s room and the school building). Meanwhile, the sixth, eighth and tenth chapter, “Twilight Boy”, “Gather Rust Cave” and “Reverse Town” were all planned under Kimura, with the latter serving as the conclusion to Yukari’s story.

Fully completing both games would unlock a secret scenario, “Prank”, a teaser to Moonlight Syndrome penned by Suda himself, making it his second chronological piece of writing after “Champion Road”.

While Suda was not the main writer, he still had a much bigger measure of control over Kyuumei-hen than he did over Tansaku-hen, meaning that the former is actually closer to Suda’s vision than Kimura’s.

In his memorandum, Kasai complained about changes that Suda implemented to his writing, and Suda was quite critical of the original scenario as well. In this E.goo interview from 2003, which I have been referencing liberally, he claims the game’s depictions of various societal ills, such as bullying or suicide, had clear-cut, easy answers, which he considered childish. Having worked as a funeral director, Suda felt that matters of death should be treated more seriously.

Obviously he’d be able to discuss it freely in 2003 since not only had he left the company by that point, it had already been dissolved. But I noticed that even in this interview from the Twilight Syndrome Official Guidebook, which would have been given while he was still a Human employee, both him and his producer espouse the credits of Investigation over Search. I find these two quotes to be especially telling.

Kobayashi: The staging in Investigation is quite a lot more refined than in the last game.

Suda: The programmers had to make effects that took loads of time to do individually for each event scene. For example, even with fade-ins, we had them create a few different versions of that. The thing I’d like people to see the most is a type of processing called overlap. It’s pretty tricky to do on the PS, but I hope those who have a bit of interest in the staging check it out. I don’t think it’s something that others are making much use of. I hope people take a look at these sorts of extravagance in Investigation.

Kumagai: We really went all out on this one.

Suda: We did everything we felt like. I think most of the things we didn’t manage to do in Search got put into Investigation.

—Did you start off with a fixed number of scenarios from the beginning and then split it into two? Or did you write scenarios as a continuation after making the first game?

Kobayashi: No, it wasn’t like that. When we went to put them all on the CD, we found that they wouldn’t fit on one disc.

Suda: Releasing it as a two-disc set meant that we had to rethink it all from scratch, so it ended up in this form. Half of Investigation is newly added stories.

—I think that a new genre has been established now that a game like Twilight has come out, and I’m sure the players want to see more come soon, even if it turns into a different sort of story.

Kumagai: Everyone says that when they try it out. I want everyone to feel that there’s more of a message, or sort of a theme, in Investigation than there is in Search.

Suda: I want people to pay attention to Chapter 6. It’s sort of, pretty… vulgar, I guess? I also think that in a way it’s sort of experimental. I wonder what kind of response we’ll get from the players after we give them that sort of message in the game. I’m kind of looking forward to that, too.

The previous director, who had left the company by that point, ended up playing Investigation and called it a kusoge (shit game). However, Suda was emboldened by the positive critical reception of the game into gaining more control over his next project. That project would be Moonlight Syndrome, released in October 1997.

While Moonlight Syndrome did follow through from the first two games, inheriting the setting of Hinashiro and the three main characters Yukari, Chisato and Mika, the game took on a completely different tone compared to the original, focusing on psychological horror rather than spiritual. That isn’t to say that the game is rooted in reality: it is the apparition of a seemingly demonic white haired boy that sends the main cast into a spiral of horror; however, the boy himself is never the initiator of violence. Rather he is a conduit for the twisted desires of those around him. Mika is now the main playing character rather than Yukari, so less time is given to her and Chisato, and a lot more of the scenario revolves around seemingly unrelated characters (the Kazan and Tohba siblings) who appear to have dragged Mika into the chaos of their lives almost by chance.

This separation is reflected in the presentation; there is a stark divide between characters who “speak” in text (as it would happen in the original Twilight) and voiced ones, with this rule being broken very slightly in certain FMV scenes. As Suda explained, this was meant to represent the divide between the world of Twilight and that of Moonlight and the characters who inhabited them. In his words, “The same characters may be looking at the same things and breathing the same air, but the scenery they see is different, their values are different, they are completely incompatible.”

This idea, that true horror would be sparked by the incompatibility between people’s views and values, was directly inspired by his experience with Kimura and other colleagues during the development of Twilight.

Tonally, the game plays out as a complete rejection of that previous project: spreading and investigating ghastly rumors was portrayed as a harmless, fun activity that high-schoolers would engage in, with the promotional radio broadcast even encouraging listeners to share ghost stories from their own towns. In Moonlight Syndrome, such activities are squarely framed as childish and disrespectful, turning other people’s suffering into entertainment, to the point where Mika’s shame for partaking in such activities due to peer pressure stands at the core of her feelings of self-loathing.

The game’s storytelling is also much more obtuse and abstract compared Suda’s previous work; in fact, the writing goes out of its way to make sure that placing its events in chronological order is impossible, events and even character traits are brought up and contradicted immediately. There is no real depiction of ghosts either, but instead a negative aura or thought that seeped into the walls of the newly urbanized Hinashiro and dragged it into a vortex of insanity.

Moreover, the game completely did away with any of the investigative elements of its predecessors; Twilight Syndrome had branching paths with different outcomes, good endings and bad endings, while Moonlight Syndrome is completely linear save for a few optional events.

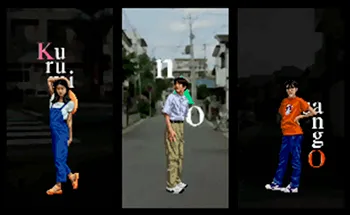

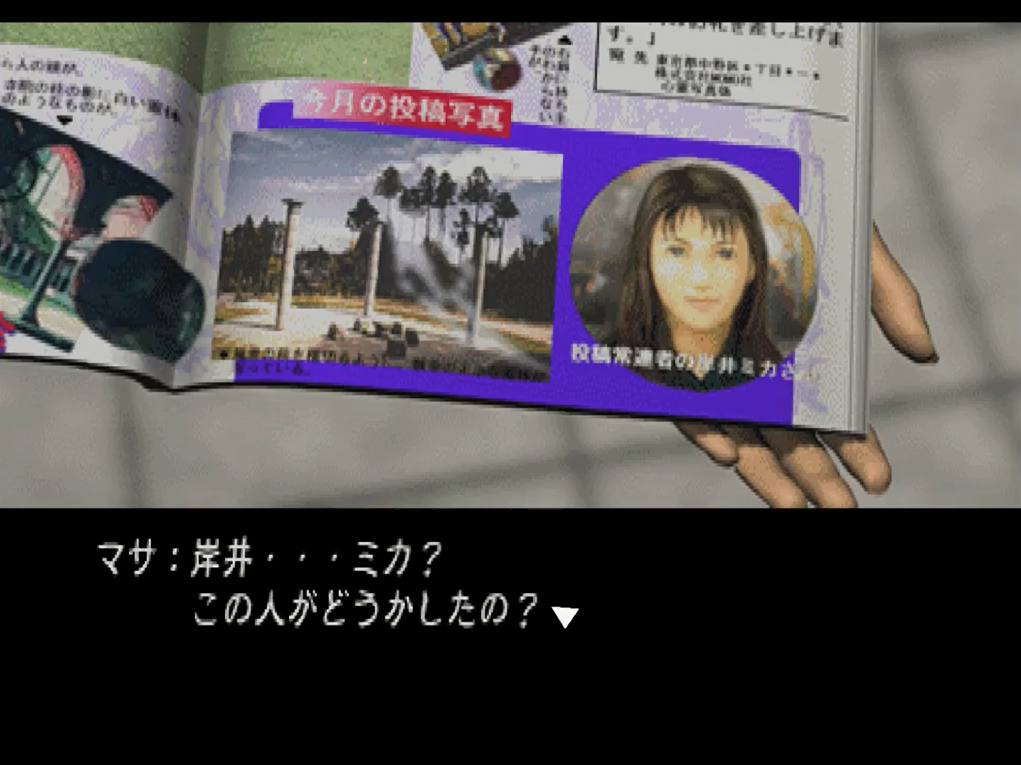

The visuals were also changed: while Twilight Syndrome relied on the digitized likenesses of real actresses (the actress for Mika even appeared in the manual of Investigation) and 2D artwork, the characters in Moonlight Syndrome are modeled after the art of Takashi Miyamoto and both the environments and the CGs are 3D renders.

To say that Moonlight Syndrome was divisive would be an understatement: the game sold decently, but it went on sale almost immediately, was lambasted by the press and while it did gain a small audience, there was nearly no overlap between Twilight and Moonlight fans. These 2ch archives are a pretty good summation of the general sentiments of the time. Common criticism include the lack of any real gameplay, the game’s obtuse storyline, and the extremely dark ending. I think one poster summarized his feelings very well when he claimed that “Suda cared more about his masturbation than he did about Twilight Syndrome fans.”

I do understand the criticism levied at it, especially when it comes to the main cast: the writing of the three main girls was the best part of the original Twilight duology in my opinion, so I can see why having their relationship being put aside could be disappointing. However I do consider Moonlight Syndrome an extremely interesting and esoteric piece of digital artwork which has worth in and of itself, especially in retrospect now that Suda spent more than twenty years building up on it, which in no way invalidates the good aspects of the previous two games.

In fact, there seems to be indications that Moonlight Syndrome was always meant as a spin-off or “alternate universe” to the rest of the series; the Twilight Syndrome: The Memorize bonus disc already depicts a future which is contradicted by Moonlight, despite it being written around the same time as Investigation’s new scenarios (One of them, “Prank”, being a teaser to Moonlight Syndrome). The game’s manual explains that while the characters of Moonlight Syndrome have been inherited from Twilight, the game itself shouldn’t be considered a sequel, but rather an independent project, with the 2003 interview published on Continue Magazine with GhM employee Masahiro Yuki and Suda reiterating this point, and that’s not even mentioning the fact that the events of the game are so abstract and metaphorical that they should be taken with a grain of salt regardless.

That being said, according to this Inverse interview, Suda’s scenario did have some level of censorship, namely due to state interference over the Kobe child murders. (Decapitation is an important motif within the game.) It’s funny to think that the scenario which offended so many people was originally going to be even more hardcore.

Due to its esoteric nature and lack of any real gameplay, ancillary publications for Moonlight Syndrome mostly focused on expanding upon or trying to make sense of the game’s story. In the months of October and November of 1997, Human released eight books dedicated to Moonlight Syndrome, an impressive number even for the pre-internet era.

The first one would be a retelling of the game’s story in the form of faux journalistic reports, titled Truth Files. Suda was not involved in its creation, and so, its contents should be taken with a grain of salt; however, it is notable for having been written by Masahi Ooka, a freelance writer hired by Human Entertainment, who would later collaborate with Suda on a variety of projects. Released on the same day, the Complete Data Files featured two short stories, this time penned by 51 himself, attempting to incorporate some elements of Moonlight’s scrapped scenarios into the existing story.

The Playstation Victory Special then featured a play-by-play description of one of said scrapped scenarios, INYAKU, which served as an alternate version of MOWDEI in earlier drafts of the game. The In-depth Guide further expanded on the unused content, featuring even more drafts and an adaptation of INYAKU as a short story again penned by 51. This controversial, poorly received game somehow even received a novelization based on an early draft on the story, deviating quite significantly from the finished product.

The other three books, which you can read about in the Merchandise section, are attempts by various authors to somehow make sense of Moonlight Syndrome through various means.

According to these interviews, during the development of Moonlight Syndrome it became obvious to Suda that Human Entertainment was going under, due to telltale signs such as delayed salaries and unpaid bonuses. In his DenFami interview he even mentions how Human’s own president was arrested for tax evasion.

He initially tried to join ASCII (who would later distribute The Silver Case) as an employee; however, ASCII’s president recommended that Suda should start his own company. He then began making preparations, including poaching some of Human’s employees, to do exactly that, leading to the foundation of Grasshopper Manufacture in March 1998.

Notable Human employees who followed Suda into his solo venture include Akihiko Ishizaka (Art director for Twilight and Moonlight), Masafumi Takada (Composer for Moonlight Syndrome), Kazuyuki Kumagai (Head of PR for Kyuumei-hen and Moonlight), Satoshi Kawakami and Kazuhisa Watanabe (Programmers for Fire Pro Special, Twilight and Moonlight). Takashi Miyamoto (Facebook, Instagram, X), the freelance artist who provided the character designs for Moonlight Syndrome, would also collaborate with GhM on several titles (namely The Silver Case, Flower, Sun and Rain, killer7 and The 25th Ward, plus providing some art for Suda51 The Complete Book and No More Heroes III) and the aforementioned Masahi Ooka, writer of the Moonlight Syndrome Truth Files, would also serve as co-writer for nearly every single Kill the Past game. Neither of them, however, joined the company as full time employees.

BigManJapan’s WORDS:

Long time ago I’ve noticed that Twilight Syndrome games’ assets are prefixed with either W or K letters. Those stand for Watanabe and Kawakami. They carried on this practice up until Killer7 game.

Killer7 source codes are prefixed like that too and it’s possible to immediately identify who coded what. Y prefix stands for Yamada Takumi who joined GhM later on and worked on Blood+: One Night Kiss and Killer7.

Suda’s instincts were ultimately proven right, as Human filed for bankruptcy in 1999 and eventually dissolved the following year.

Due to the reasons listed above, Moonlight Syndrome went on to be completely ignored by the rest of the Twilight Syndrome series, despite ending on a cliffhanger. After Suda had left, the two halves of Twilight Syndrome were finally brought together as one with the July 1998 release of Twilight Syndrome Special. Moonlight Syndrome was not included in this compilation, and according to this 2ch thread (post 211), the game was even removed from Human Entertainment’s website, though this claim can’t be verified since the only functioning archive of Human’s software page predates its release.

Development then began on a sequel to the original Twilight Syndrome, tentatively titled “Twilight Syndrome 2”. While no information on the game ever leaked and its development was halted by Human’s bankruptcy, the one pre-release screenshot we have access to (depicting the new protagonist) seems to imply that it would have been similar, if not identical, to the later Twilight Syndrome: Reunion. That, combined with the timing of its release, suggests that the game would have sidestepped or ignored the events of Moonlight entirely.

The cryptic cliffhanger ending of Moonlight Syndrome would not remain without a follow-up however; its story was continued in Grasshopper Manufacture’s first game, The Silver Case, released in October 1999.

The setting of Moonlight Syndrome would be expanded upon in said game, eventually growing into the Kill the Past series itself; the full moon imagery, the interpretation of ghosts as “remnant psyches” (残留思念), the obtuse and cryptic storytelling, the use of television screens as spiritual mediums, all of that informed what came after in Suda’s career. As late as 2018 Moonlight Syndrome was still being referenced directly in Suda’s work, meaning that while the game itself may be “forgotten”, its legacy is very much alive.

Funnily enough, a spiritual sequel to Twilight Syndrome called “Yuuyami Doori Tankentai” was released by Spike on the exact same day as The Silver Case.

Being developed by team YURA and EXIT inc., the game was advertised as sharing the same staff as the original Twilight. However, comparing the credits (Search, Investigation, Yuuyami) seems to indicate that only Keita Kimura (the original director) and Mika Mishima (the writer in charge of editing the girls’ dialogue) overlapped between the two projects, with programmer Kenichi Matsuda only being credited among the “Special Thanks” in the original Twilight Syndrome. Due to a series of bizarre business decisions and court cases which would honestly deserve their own website to be chronicled, team YURA disappeared off the map.

Spike eventually acquired the rights to the Twilight Syndrome brand itself.

July 2000 saw the release of Twilight Syndrome: Reunion (Saikai); it is unknown how far development had gotten under Human Entertainment, but Reunion contradicts the events of Moonlight Syndrome outright in its first chapter, and reframes the Twilight Syndrome franchise as an anthology series by starring a different set of high-schoolers in a different town.

Reunion was followed by a sequel film, “Graduation”, released just six months after. (Yuri’s friends in the movie happen to be called Mika and Chisato; they are not, however, the same girls as the original game.)

There were plans to release a new Twilight Syndrome game on Playstation 2 around 2006, but those plans never came to fruition. The series was revived one more time in July 2008 with the release of “Forbidden Urban Legends” on the Nintendo DS, again following a new cast of high-schoolers, but this time being set in Tokyo instead of a small town due to its focus on urban myths. Once more, Forbidden Urban Legends ignores the events of Moonlight Syndrome by depicting the older version of a character who died in said game, cementing that the Syndrome series and the Kill the Past series are in fact separate and running in parallel. The Nintendo DS release was also followed by two movies, “Dead Cruise” and “Dead Go Round”, however said movies take place in the “real world” where the main characters play the game Forbidden Urban Legends on their Nintendo DS.

Twilight Syndrome would be referenced one last time in Super Danganronpa 2. In one of its cases, Twilight Syndrome appears as an arcade game programmed by Monokuma (the game’s villain) to hint at one of the character’s past deeds. By the time of its release (July 2012) many GhM employees, some of them veterans who met Suda while working on Twilight Syndrome, were working under Spike-Chunsoft and collaborated on the development of Danganronpa, most notably Akihiko Ishizaka and Masafumi Takada.